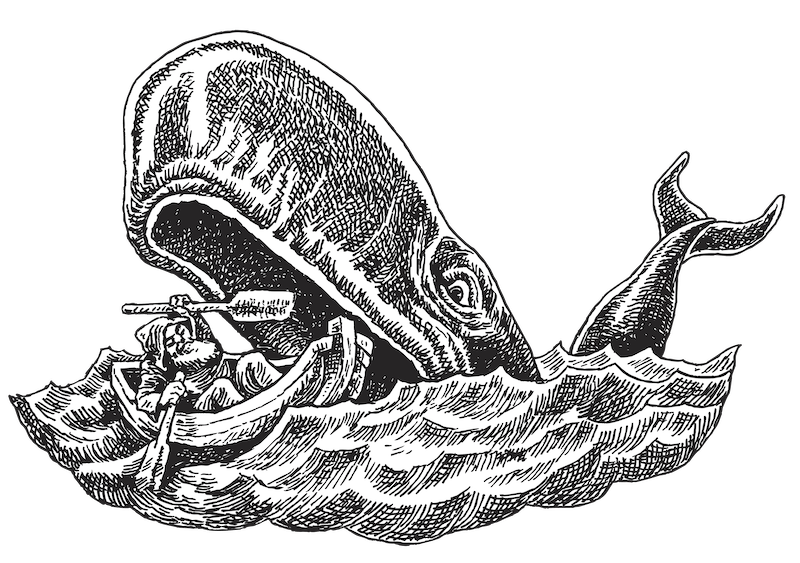

the deluge

ABOUT COMMENTS BOOK CONTACT BACK

The world is full of mediocrity.

We might think that we know this already. But do we? When institutions optimize for efficiency and scalability, excellence becomes a statistical outlier rather than a goal. It has been argued that in history societies have suppressed or rejected the exceptional individuals — the Übermenschen — in favor of safety, comfort and uniformity. What really is exceptionality and what does the German word tell us about our species? We have created a civilizational architecture that tends toward the mean, not the contrarian. But the author posits that mediocrity is a human condition and nothing can be done about it. Although there tends to be natural opposition to discordant ideas which may or may not pick up traction, it must not be confused with excellence by virtue which is an innate faculty. One is either born with it or not.As societies or groups, prosperity is often seen as a result of size, culture, values and mobility. The Jews thrived not because they were special but because they were minorities and they had to work hard to stand out. In contrast, the same wasn't observed among the Black community despite extended opportunities and some still see the majority as "ghetto". Flourishing demands sustained effort, sacrifice and dissatisfaction — qualities most humans avoid to preserve ease or minimize pain. This has got nothing to do with excellence as a faculty but has a lot to do with excellence as a goal, which sadly cannot compensate for mediocrity as a species.

The world is full of stupidity.

Someone is noted to have quoted, "Everyone who talks about stupidity presupposes that he is above things, i.e. that he is clever, although it is precisely this presumption that is considered a sign of stupidity". It is apparent that rather disagreeable, derisive gentlemen of this kind whose names the author neither knows nor is interested in finding out of course don't understand the difference between calling people stupid and observing the world in which stupidity has always abounded in a rational discourse. Or he reckons they themselves aren't bright.We are living in an era of Artificial Intelligence. Sadly there is nothing inherently intelligent about it. The coinage is of poor taste as the two words are mutually incongruent. Some of us will surely chuckle if the author asks: why not call it Synthetic Intelligence? Huge sums of money are flowing while a Meta hire has gone announcing "superintelligence". The author of course puts this in the same enthusiasm league as Alphabet's "singularity". Meanwhile, robotaxis have started driving themselves given that asphalt roads were historically created for humans at the wheel. The author thinks we will keep producing electric cars until we run out of Lithium, and we will keep calling our desktops, laptops and workstations as "computers" which are not really electronic abacuses.

The world is absolutely messy.

Humans are flawed agents of order driven by partial knowledge, self-interest and conflicting desires. It has been argued that we may even come to prefer comfortable illusions to facing the truth of messiness. From a broad perspective, researchers who studied bee colonies and ant hives have correlated this to entropy, or the tendency of systems to move from order to disorder and ambiguity, or resistance to simple categories or neat solutions. Postmodern views state that the world is messy because every order is partial, contested and constructed. As a result of this, borders shift, alliances break, ideologies clash; the market becomes a messy, unpredictable beast: booms, crashes and bubbles; cultures mix and clash, but understanding lags behind.The author on the other hand suggests that a messy world is unlike a neat cosmos because it lacks wise order. He also believes that humans are largely emotional animals trying to run rational institutions. Our competing values viz. secular, religious, traditional, progressive and the absence of shared meaning breeds cynicism, relativism and moral exhaustion. Further, he says that injudicious interventions can produce unintended side effects. Often this is a tragedy of good intentions e.g. medical interventions that created antibiotic resistance.

The deserving don’t necessarily get rewarded.

To begin with, this isn't about fairness or whether we live in a just world, as majority would already be thinking. This is more of a question about merit vs. chance and how life happens for humans. It is true that the worthy may be overlooked because of nepotism where rewards go to the connected, not the competent, bureaucracy where systems value form over substance, and short-term thinking where flashy performers are rewarded over steady contributors. But it is also true that effort and worthiness do not guarantee result because life operates through complicated, interacting forces that no one fully controls.As the author believes, many of us live in illusion, unable to see true merit, and herd values often comfort over greatness. It has been argued that birth is the ultimate unfair advantage. A child born to educated parents in premier monde (first world) with good institutions has won a lottery they didn't even know they were playing. Meanwhile, equally talented children born into poverty or dysfunctional societies face obstacles that no amount of individual merit can overcome. Interestingly, success compounds in ways that have little to do with merit. Once someone achieves initial recognition, often through luck or connections, they gain access to better opportunities, more resources and influential networks. This creates a feedback loop where early advantages, however small or undeserved, snowball into massive disparities.

Science is not a creative or intuitive discipline.

Many would consider this highly contentious and argue vehemently that science is a deeply creative and intuitive endeavor without understanding the premise deeply. But the author explains why it is not and rather is foremost, observational and experimental. This is because the scientific method demands precision, repeatability and falsifiability — not wanton creativity. It is obvious that intuition and truth will align if the science is "good", a delicate notion which very few will understand. But it prioritizes objective truth and is always held in check by the demands of evidence and reason. Further, scientific discoveries are made within communities of inquiry — peer review, reproducibility, consensus. The lone discoverer is less important than the network of validation, and it is one of the two reasons why the author believes that good science is hard, the other being that it advances through small, careful additions to existing knowledge, radical leaps being rare.There are arguments from humans and examples in history demonstrating why science does not obey intuition. These are mainly in quantum mechanics and relativity. Einstein rejected quantum indeterminacy because he intuitively believed in a deterministic universe. Does this mean he did not believe that nature at its core was probabilistic? Newton’s intuitive model of immutable space and time collapsed under relativity. Schrödinger was intuitively uncomfortable with the idea that a system could exist in a superposition of macroscopically distinct states. Experiments in quantum mechanics confirmed quantum weirdness scales beyond what Schrödinger imagined. But do these examples fall under the purview of good science or bad science? Sadly the author hasn't verified.

Democracy is futile.

The term democracy first appeared in ancient Greek political and philosophical thought in Athens during classical antiquity. The word originated from "dêmos" (common people) and "krátos" (force) to mean "rule of the people". Greek democracy assumed that through rational discourse and philosophical reflection, citizens could discover universal truths about justice, virtue and the common good. The Socratic method was designed to reveal these eternal verities through dialogue among equals who shared common cultural assumptions. Modern epistemology, shaped by the scientific revolution and postmodern critique, has shattered this confidence in accessible universal truth. We now understand knowledge as probabilistic, culturally constructed, and domain-specific. The explosion of specialized knowledge means no individual can meaningfully grasp the full complications of modern governance.Modern democracy operates in an information environment where sophisticated actors can manufacture consent through targeted propaganda. Voters believe they're making independent choices, but their preferences are shaped by billion-dollar influence campaigns designed to exploit cognitive biases. Policy questions get bundled into partisan packages that force voters to accept positions they disagree with in order to support positions they care about. Most voters also lack the time, expertise or cognitive capacity to meaningfully evaluate these complicated policy questions. Democratic selection doesn't optimize for competence. It optimizes for popularity. The skills needed to win elections have little overlap with the skills needed to govern effectively. The author believes a more complex, revised system could solve democratic issues across developed nations.

There is little harmony between sexes.

Modern gender theory has largely embraced social constructivism, the idea that gender roles are culturally created rather than naturally given. But the author thinks this is flawed and equality is a constructed myth. As a result, men who derived identity and purpose from traditional provider or protector roles struggle to find meaning in egalitarian arrangements. Women who gained access to formerly male domains often face the double burden of maintaining both career success and domestic responsibilities.The author believes that erosion of feminine values have made women more prone to power struggle and identity crisis. More and more women want men to be allies while continuing to support primarily fellow women in society and workplaces. He calls it the "power-purpose conflict". The bedroom has become another arena where power must be negotiated rather than a space where different energies naturally complement each other. Men are asked to acknowledge male privilege and step back from traditional masculine dominance while also being expected to maintain attractive masculine confidence. Most fundamentally, contemporary gender relations lack a coherent philosophical foundation and according to the author, the cause is Feminist ideology.

The world is directionless.

If there is no built-in purpose to nature or history, then it is plausible that the world has no inherent direction. Indeed, history lacks intrinsic purpose and evolution works by blind chance and necessity. Contemporary culture exists in what sociologists call "liquid modernity", a perpetual present where the past seems irrelevant and the future unpredictable. Without temporal anchoring, human life loses narrative coherence and directional momentum. No shared global ethic binds humanity.We have seen that the world did benefit from technology leading in the West but the trade-off has been compromise in quality and superfluity. The author states how the USA built reliance on the Far East which, once driven by economics and cheap labor, has now morphed into trade wars and embodies directionless conflict and a struggle for control and dominance. The result is a "sharp reconfiguration of global value chains" that makes the system "less efficient and more opaque". In the UK, Brexit was framed as taking back control. The author believes that this also stemmed from a sentiment of independence and nationalism among the population and the leading idea among a few that home-grown products can be developed better and economy can be boosted. The aftermath shows confusion and fragmentation: internal division, uncertain alliances, unclear goals, resulting in subsequent attempts of renegotiation with the EU. The author considers this a folly and directionless failure on a national scale.

The world lacks collective foresight.

Human consciousness evolved for immediate environments where cause and effect unfolded within observable timeframes. We could see that overhunting depleted game, that poor harvests followed bad weather, that tribal conflicts had direct consequences. In the modern world, collective foresight requires coordinating millions of individual temporal perspectives into coherent shared vision, and our institutions systematically prevent this coordination. Nations, corporations, communities pursue short-term interests, not shared futures.The COVID-19 pandemic perfectly illustrates collective foresight failure. Epidemiologists had predicted pandemic risks for decades. Yet when COVID-19 emerged, the world responded with shocked improvisation rather than executing prepared plans. This wasn't due to lack of information but rather the philosophical impossibility of maintaining institutional attention on low-probability, high-impact events that might never occur within any individual decision-maker's tenure. The 2008 economic crash arose in part because experts believed complex financial instruments such as derivatives and credit swaps were well understood and low-risk. Perhaps most fundamentally, collective foresight failure reflects what philosophers might call the "temporal sovereignty problem", the question of how present generations can make binding commitments for future ones. Starkly, we've created nuclear arsenals capable of ending human civilization while developing no coherent philosophy for managing this capability across generations. The author notes that every developed society exhibits the same pattern: building infrastructure during periods of optimism and prosperity, then neglecting oversight during periods of fiscal constraint, leading to predictable system failures decades later.

The Deluge: That Which Shall Save The World. The author notes that "genius" is a word that has grown to become ubiquitous since the 19th century. Looking at its origin, he enlightens us to see that genius comes from the root gene which means to give birth. In its appropriate use, genius would mean Father: the male spirit of a gens — the one with "generative power". In a mundane world that has always been full of harlequins and ignoramuses, who are we to say who was or is a genius?Jayden Armenson has been called "the most important intellectual and philosopher of our times" by selected historians. His empyrean visions and diaphanous ideas have earned him God-like status among a few. The numbers are only growing. He is a revered savant and an Esprit de Renaissance. Read his wiki.

Check back later.

When comments are added they will appear here. Go to "Contact".